- This post was written entirely from the brain and heart of a real, flesh-and-blood, ensouled human being, with zero ideas, input or editing from AI. All artwork is credited to the original, human creators. I will never willingly outsource my brain to AI. EVER. -

Dear friend,

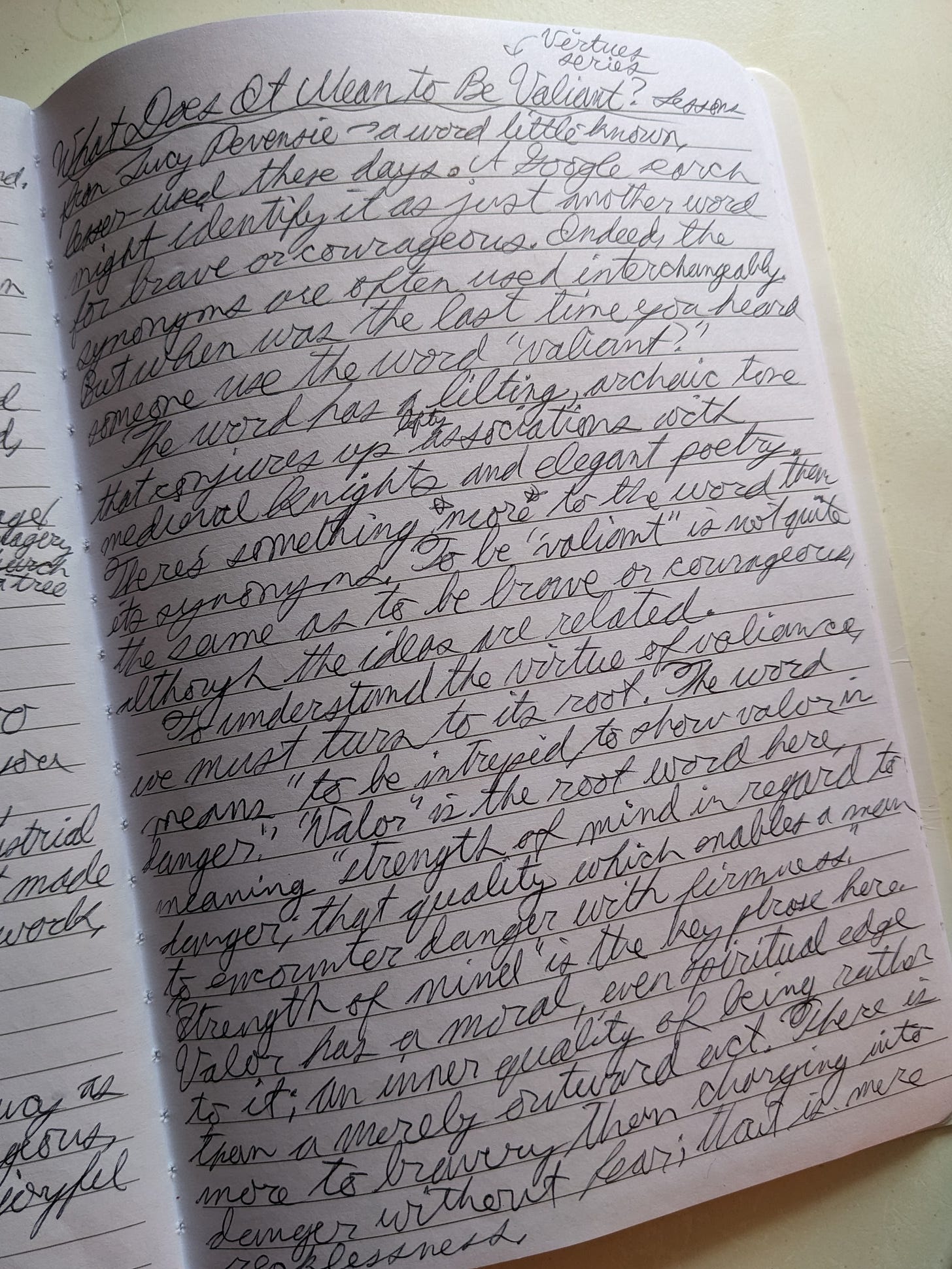

I wrote this post in one hour-long sitting in the front passenger seat of my family’s RV, coming home from a weekend camping trip with my dad. Feet tucked up on the seat, window cracked, summer breeze ruffling my hair, I curled in the corner and scribbled away in my notebook. I’ve included a photo of the draft at the end of this post. The idea popped into my brain while I sat gazing out at the Virginia scrub pines, mom-and-pop farmstands, and little white churches flying past, and I simply had to get it down on paper. Sometimes thoughts just take possession of you. When the writing itch calls, the writer must obey.

Perhaps I’ll make this post the first in a series on the virtues. Maybe. But for now, enjoy my reflections on the virtue of valiance and what it means to be valiant.

Valiant.

It’s a word little-known, less-used these days. A Google search might identify it as just another term for brave or courageous. Indeed, the synonyms are often used interchangeably. But when was the last time you heard someone use the word “valiant”?

The word has a lilting, archaic tone that conjures up lofty associations with medieval knights and elegant poetry. There’s something more to the word than to its synonyms. To be valiant is not quite the same as to be brave or courageous, although the ideas are related.

To understand the virtue of valiance, we must turn to its root. The word means “bravery and determination, especially when things are difficult, or when the situation gives no cause for hope.”1 Valor is the root word here, meaning “strength of mind in regard to danger; that quality which enables a man to encounter danger with firmness.”2 “Strength of mind” is the key phrase here. Valor has a moral even spiritual edge to it; an inner quality of being rather than a merely outward act. There is more to bravery than charging into danger without fear: that is mere recklessness.

Even the dictionary definition is inadequate, however. It fails to get at that spiritual, near-mythical quality associated with the idea of “valiant.” Like any virtue, it cannot be fully apprehended through bland, rationalized definition: fact presentation stripped of all wonder and beauty. Virtue (Latin virtus from vir (man) - moral strength, quality of character) is a matter of the heart, not the head. All the fact-memorization in the world won’t cultivate virtue in a person if it does not take root in his heart. It must capture his or her imagination. One must understand valiance through beholding characters presented to him whom he can sympathize with, admire, and desire to imitate.

And for that, we need story.

Let’s thus look at what it means to be valiant by examining characters in classic literature and history to whom the word applies. I want to understand this and other virtues for myself, that I might become more valiant, honest, joyful, loving, kind, etc., in my own life. The good is a life of greater integrity to the glory of God, that I would become more like Christ.

In this post, I get to look at one of my favorite literary heroines, Queen Lucy the Valiant of Narnia, and one of the most inspirational (and mythical) American presidents, Theodore Roosevelt. Part 1 of this post will be dedicated to Lucy and examine her valiance in the hopes she teaches us something of her ways, especially as a woman. Part 2 will center around Roosevelt’s speech “Citizenship in a Republic” and a certain quote that approaches the more masculine side of valiance. Both understandings offer value for both men and women, however. Hopefully by studying these two examples, we can glean a bit of wisdom for how to be valiant, here and now.

Part 1: Lucy Pevensie: Valiant in Faith

Have you ever wondered why C.S. Lewis gave the titles he did to the four Pevensie children? Surely any number of adjectives could have suited these characters. While it’s easier to understand Edmund “the Just” or Susan “the Gentle”, why is a twelve to fourteen-year-old boy crowned “High King Peter the Magnificent”? A weighty title for a boy barely entering puberty. Or better yet, why is a six-year-old girl the Valiant Queen?

While it is true that the children grow into their titles as they age, the monikers are not mere wishful thinking. Lewis is intentional with these names as with everything else in his books. He knows that names have power and meaning. To call Lucy “valiant” is not just an expectation. It’s a description. Lucy Pevensie is valiant, now, and always has been. Lewis makes it her defining trait:

But as for Lucy, she was always gay and golden-haired, and all princes in those parts desired her to be their Queen, and her own people called her Queen Lucy the Valiant.

(The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, p. 192)

Surely the other children are valiant too? If Lucy is “gay and golden-haired,” would not “the Joyful,” or “Sweet,” “Merry,” “Lovely” fit her better? No, they would not. For, while apt descriptions, they do not convey the essence of Lucy’s character in the story. Valiance, or “bravery or determination when the situation gives no cause for hope,” is at the core of who Lucy is.

She is the first Pevensie child to step through the wardrobe into the land of Narnia. Although she is “a little frightened”3 at first, her intrepid curiosity leads her onward. She steps out into the unknown (a brave act that many of us never take), and in doing so catalyzes the entire story. She moves in faith, even though said faith is subtle, hidden beneath her inquisitiveness at first. Without that faith, the story’s events would not unfold.

Throughout the series, Lucy consistently shows boldness and willingness to be different for the sake of what is right. She accepts the fantastical impossibility of Narnia with ease. When she encounters Mr. Tumnus - a strange magical creature with unknown intentions in a bizarre new world - Lucy befriends him naturally. I suspect not many of us would follow suit. When he is taken prisoner and the four siblings debate what to do, Lucy insists they try to rescue him against all odds - as opposed to Susan’s nervous hesitancy. Lucy is the instigator, the curious and daring youngest child. As an adult, she rides to battle and fights with the archers - the Valiant Queen:

a fair-haired lady with a very merry face who wore a helmet and a mail shirt and carried a bow across her shoulder and a quiver full of arrows at her side.

(The Horse and His Boy, p. 176)

In a uniquely feminine way, Lucy is a fighter - and a healer too: her defining gift from Father Christmas is the magical cordial that saves Edmund. She shows courage in the face of evil beyond the battlefield. Her tenacity is soul-deep.

Valiance is not about mere physical strength or prowess in battle. It has a spiritual cast that comes from faith. Out of all Narnia’s characters, Lucy most obviously and consistently exhibits faith. When we encounter Aslan mostly through her eyes, we see that she is the primary heroine because she shared a relationship with him akin to that of Jesus and John the Beloved Disciple. In Prince Caspian, Lucy is the one whom Aslan calls through the powerful bond of her faith. The others remain unawakened yet to the Hidden Music, but Lucy is the first to wake up. When the other children don’t believe her again and again, overcoming their skepticism and even ridicule takes immense courage. Her ideas seem nonsensical to the others at first, but her persistent belief and urging ultimately leads them to shed their blindness and understand. Holding to one’s convictions in the face of pushback - that is valiant indeed. Lucy’s valiant faith leads others to Aslan.

Vigen Guroian provides an excellent analysis of Lucy’s faith in Tending the Heart of Virtue: How Classic Stories Awaken a Child’s Moral Imagination:

Lucy is the one who sees, as her name implies. she sees the fresh water stream and the apple trees near the castle ruins of Cair Paravel. She is the first to see the walls of the ruins. And when Peter challenges the children to guess where they are, Lucy responds: “Go on, go on…I’ve felt for hours that there was some wonderful mystery hanging over this place.” (pp. 18-19)

(Guroian, p. 166)

Through Lucy, we learn that valiance is courage fueled by faith. Belief in a greater power, a higher good, or a worthy goal makes the timid child into a Valiant Queen, doing brave deeds of all kinds because the Lion has made her a lioness. There is a high nobility to the idea of being valiant that mere bravery doesn’t quite get at.

As a friend of mine put it, Lucy has a “sensitivity” to the world of Narnia, and especially to Aslan. Her simple, innocent and spunky faith inspires those around her and leads the way “further up and further in.” That is why she is named “Valiant.” A worthy ideal for young girls to emulate. I even plan to name my first daughter “Lucy," after one of my favorite heroines.

Light-hearted courage in defiance of the dark unknown, against unfriendly odds. To defy evil and uphold the good. To be gracious, winsome and faithful when the entire world howls at you, demanding that you cease…that is valiance.

Part 2: Theodore Roosevelt: The Man in the Arena

We need not look only to literary characters to find worthy models of what it means to be valiant. Great figures from history can also serve as guides and teachers. One of the most famous and beloved beacons of a particularly fierce, masculine brand of valiance was Theodore Roosevelt. (I take no credit for this section: the same friend mentioned above brought Teddy to my attention, describing him as a great role model for how a man (or a woman, but especially a man) can show true valor.

In one of his famous speeches, “Citizenship in a Republic,” Roosevelt describes what a true fighter looks like:

“It is not the critic who counts; not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles, or where the doer of deeds could have done them better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly; who errs, who comes short again and again, because there is no effort without error and shortcoming; but who does actually strive to do the deeds; who knows great enthusiasms, the great devotions; who spend himself in a worthy cause; who at the best knows in the end the triumph of high achievement, and who at the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who neither know victory nor defeat.”

True courage means putting everything, even one’s life, on the line for what is right. It’s getting down in the trenches, expending effort even though failure may come again and again. To be valiant is to encounter resistance and stand firm, pushing through for a worthy cause. It’s not the absence of fear, but “doing it anyway” despite the fear, no matter the odds. To be valiant is to be passionately, purposefully brave in the face of one’s enemy.

And here, I come, I think, to the heart of valiance. It is bravery rooted in love. Whether the object of love is one’s God, country, family, people or principles…one cannot be called valiant unless one’s heart is engaged in the fight. The love may behind you or in front of you. You may strive to seek or to protect. The deed may be daringly majestic or quietly ordinary. But every single time you choose faith over fear, love over complacency…you are indeed “the Valiant.”

The good news is, dear friend: you are not alone in this fight. We have a Captain, a great High King who leads the way and shows us the path forward. He fights alongside us in our various small battles because He has fought and won the greatest and final battle. The victory over Death is secured, sin’s dominion broken. Any worldly circumstance that calls us to be valiant is only one of evil’s death throes, a last-ditch effort to grasp at your soul.

When that happens, our Lord is strong to save. He will deliver you and bear you up. You need only to surrender and trust Him. To count the cost and choose Him. That trust is the spark that will roar into a flame of faithful courage if properly fed.

Fear not, for I am with you; be not dismayed, for I am your God; I will strengthen you, I will help you, I will uphold you with my righteous right hand.

Isaiah 41:10

In The Return of the King, J.R.R. Tolkien describes the charge of the Rohirrim at the Battle of Pelennor Fields as they ride to aid the ailing Minas Tirith. They fight fiercely, boldly, although they have every reason to fear, and many will die in the battle. And yet, they do more than fight with courage.

They sing with joy.

“And then all the host of Rohan burst into song, and they sang as they slew, for the joy of battle was on them, and the sound of their singing that was fair and terrible came even to the City.”

(The Lord of the Rings, Book V, p. 838)

Be Valiant.

Fear Not.

“But seek first the Kingdom of God and His righteousness, and all these things will be added to you as well.” -Matthew 6:33

-Laura

The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, p. 16.

That was a wonderful article. Teddy certainly has some phenomenal speeches.

Sounds like you’ve got a great friend!